All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

An Arabidopsis Maternal Effect Embryo Arrest Protein is an Adenylyl Cyclase with Predicted Roles in Embryo Development and Response to Abiotic Stress

Abstract

Background:

Second messengers play a key role in linking environmental stimuli to cellular responses. One such messenger, 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) generated by adenylyl cyclase (AC), has long been established as an essential signaling molecule in many physiological processes of higher plants, including growth, development, and stress response. Very few ACs have been identified in plants so far, so more must be sought.

Objective:

To test the probable AC activity of an Arabidopsis MEE (AtMEE) protein and infer its function bioinformatically.

Methods:

A truncated version of the AtMEE protein (encoded by At2g34780 gene) harboring the annotated AC catalytic center (AtMEE-AC) was cloned and expressed in BL21 Star pLysS Escherichia coli cells followed by its purification using the nickel-nitriloacetic acid (Ni-NTA) affinity system. The purified protein was tested for its probable in vitro AC activity by enzyme immunoassay. The AtMEE-AC protein was also expressed in the SP850 mutant E. coli strain, followed by an assessment (visually) of its ability to complement the AC-deficiency (cyaA mutation) in this mutant. Finally, the AtMEE protein was analyzed bioinformatically to infer its probable biological function(s).

Results:

AtMEE is an AC molecule whose in vitro activity is Mn2+-dependent and positively modulated by NaF. Moreover, AtMEE is capable of complementing the AC-deficiency (cyaA) mutation in the SP850 mutant strain. AtMEE is primarily involved in embryo development and also specifically expressed in response to abiotic stress via the MYB expression core motif signaled by cAMP.

Conclusion:

AtMEE is an AC protein whose functions are associated with embryo development and response to abiotic stress.

1. INTRODUCTION

3ʹ,5ʹ-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) is the typical prototype second messenger molecule in all living organisms ranging from prokaryotes (e.g., Escherichia coli) to the complex multicellular Homo sapiens [1-4] and the cellular enzyme, adenylyl cyclase (AC) being its sole source. In bacteria, cAMP is involved in the positive regulation of the lac operon, where, in an environment of low glucose, it accumulates and binds to the allosteric site of the transcription activator protein (CRP). Once the CRP is activated, it will bind to a cis-element upstream of the lac promoter and activates transcription [5]. In fungi, cAMP is involved in the development of the slime mold Dictyostelium discoideum, which grows either as a unicellular or multicellular organism, where cAMP signaling responses mediate the critical processes of cell sorting, pattern formation and morphogenetic changes [6]. In animals, cAMP can be readily incorporated into various hormonal cascades, controlling several processes, such as cardiac contractility and neurotransmitter release [7]. In plants, many processes that are cAMP-dependent have been reported, among them include control of the cell cycle and stress response in tobacco [8, 9], transport of sodium ions via voltage-independent channels (VICs) in Arabidopsis thaliana [10], stomatal closure in Vicia faba [11], growth of pollen tubes in Agapanthus umbellatus, Lilium longiflorum and Zea mays [1, 12] and activation of the phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) enzyme in French beans [13]. Nevertheless, very few ACs have been identified in plants.

In higher plants, the first ever AC was identified in 2001 in maize, using recombinant expression and complementation testing systems, and this protein, Z. mays pollen signaling protein (ZmPSiP), was found to be responsible for the polarized growth and re-orientation of pollen tubes [1]. Subsequent to that, in 2010, Gehring used a search motif based on the functionally assigned amino acids in the catalytic center of annotated and/or experimentally tested nucleotide cyclases (NCs) in lower and higher eukaryotes to search the Arabidopsis genome and a number of probable AC candidates were reported [14]. Among them, were a pentatricopeptide repeat protein (AtPPR-AC) and clathrin assembly protein (AtClAP) that have since been experimentally confirmed as functional ACs [15, 16], and a maternal effect embryo arrest protein (AtMEE), which we targeted for this study and report herein. AtPPR-AC is annotated to play a role in chloroplast biogenesis and restoration of cytoplasmic male sterility [15], while AtClAP is predicted to have a role in endocytosis and plant defense [16].

Based on the same AC motif search strategy [14], five more ACs were identified, four in Arabidopsis and one in Z. mays. The Arabidopsis ACs include two permeases (AtKUP7 and AtKUP5) responsible for K+ ion uptake [17, 18], a leucine-rich repeat protein (AtLRRAC1) responsible for pathogen defense [19, 20], and a 9-cis-epoxycarotenoid dioxygenase (AtNCED3) involved in the biosynthesis of the stress hormone abscisic acid (ABA) [21]. The Z. mays AC is a putative disease-resistance RPP13-like protein 3 (ZmRPP13-LK3), which participates in ABA-mediated resistance to heat stress [22]. In addition to these eight identified ACs, two more were identified, namely, a Nicotiana benthamiana adenylyl cyclase protein (NbAC) responsible for tabtoxinine-β-lactam-induced cell death during wildfire diseases [9] and a Hippeastrum hybridum adenylyl cyclase protein (HpAC) involved in stress response and cell signaling [23]. Notably besides these ten higher plants ACs, one additional lower plant AC was also identified in the form of a Marchantia polymorpha AC (MpCAPE) protein with a role in cell and male organ development [24].

Apparently, the current noticeable scarcity of identified ACs in plants implies that their genes might be camouflaged within a wide range of large gene families and that they might also vary regarding their expression, structure, activity and regulation [22]. Therefore, in pursuit of identifying yet another plant AC, we hereby detail the cloning, expression, and affinity purification of a truncated version of the AtMEE protein (AtMEE-AC) and report on its inherent activity as an AC as well as elucidating on its inferred functional role in embryogenesis and abiotic stress response.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. AtMEE Protein Sequence

The complete amino acid sequence of the AtMEE protein was retrieved from The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR) (https://www.arabidopsis.org/) and analyzed for the presence of the AC catalytic center using the PROSITE database located within the Expert Protein Analysis System (ExPASy) proteomics server (https://www.expasy.org/).

2.2. Cloning and Expression of the AtMEE-AC Protein

Total RNA was extracted from six-week-old Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia-0 (Col-0) seedlings using the RNeasy plant mini kit, in combination with DNase 1 treatment, as instructed by the manufacturer (Qiagen, Crawley, UK). At2g34780 (AtMEE) copy DNA (cDNA) synthesis from the total RNA and subsequent amplification of the AtMEE-AC gene fragment from the cDNA were simultaneously performed in the presence of two sequence-specific primers (forward: 5′-GCCCGGAAGGATCCAATGTCGGAGTTGGAGGTG-3′ incorporating a BamHI restriction site and reverse: 5′-GCGCCGGAATTCCGAGACTAATTGCGCTTCTTG -3′ incorporating an EcoRI restriction site), using a Verso 1-Step RT-PCR kit and in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, USA). The PCR product was then cloned into the pCRT7/NT-TOPO expression vector (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) to make a pCRT7/NT-TOPO:AtMEE-AC fusion expression construct with an N-terminal His purification tag. For expression of the recombinant AtMEE-AC protein, competent Escherichia coli BL21 Star pLysS cells (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, USA) were transformed (through heat shock at 42°C for 2 min) with the pCRT7/NT-TOPO:AtMEE-AC fusion constructs and grown in double strength yeast-tryptone (2YT) media (16 g/L tryptone, 10 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl and 4 g/L glucose; pH 7.0) containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin and 34 µg/ml chloramphenicol, on an orbital shaker (250 rpm) at 37°C. Protein expression was induced by the addition of isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG, Sigma-Aldrich Corp., Missouri, USA) to a final concentration of 1 mM and when the optical density (OD600) of the cell culture had reached 0.5 (approximately 3 h). The culture was left to grow for 3 h at 37°C.

2.3. Purification of the AtMEE-AC Protein

The resultant expressed recombinant AtMEE-AC protein was purified by preparing a cleared cell lysate of the induced E. coli cells under non-native denaturing conditions, where the harvested cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (8 M urea, 100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris-Cl; pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 7.5% (v/v) glycerol) at a ratio of 1 g pellet weight to every 10 ml buffer volume, mixed thoroughly using a mechanical stirrer at 24°C for 1 h and then centrifuged at 2500xg for 15 min. The supernatant was collected as the cleared lysate and transferred to 2 ml of 50% (w/v) Ni-NTA slurry (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., Missouri, USA) that had been pre-equilibrated with 10 ml of lysis buffer and then gently mixed on a rotary mixer for 1 h at 24°C. This step allowed for the binding of the protein to the Ni-NTA resin. The lysate-resin mixture was loaded into an empty XK16 column (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., California, USA), allowed to settle, and the flow-through was discarded. The protein-bound resin was then washed three times with 30 ml of wash buffer (8 M urea, 100 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM Tris-Cl; pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 7.5% (v/v) glycerol, and 40 mM imidazole) to remove unbound proteins.

2.4. Refolding of the AtMEE-AC Protein

The washed protein-bound resin was equilibrated with 2 ml of gradient buffer (8 M urea, 200 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-Cl; pH 8.0, and 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol) before the column was connected to a Bio-Logic F40 Duo-Flow chromatography system (Bio-Rad Laboratories Inc., California, USA) programmed to run a linear refolding gradient. The refolding gradient for the denatured recombinant AtMEE-AC was then performed by linearly diluting the 8 M gradient buffer to 0 M urea concentration with a refolding buffer (200 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-Cl; pH 8.0, 500 mM glucose, 0.05% (w/v) poly-ethyl glycol, 4 mM reduced glutathione, 0.04 mM oxidized glutathione, 100 mM non-detergent sulfobateine, and 0.5 mM phenylmethanesulfonylfluoride (PMSF) over 10 h at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min. After refolding, the renatured recombinant protein was eluted in 2 ml of elution buffer (200 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-Cl; pH 8.0, 250 mM imidazole, 20% (v/v) glycerol, and 0.5 mM PMSF). The eluted native protein fraction was then de-salted and concentrated using a Spin-XUF filtration/concentration device and in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (Corning Corp. New York, USA) with a molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) point of 3000 da. Protein concentration was determined by the Bradford method [25] and ND2000 nanodrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Inc., Massachusetts, USA) before the recombinant protein was stored at -20°C.

2.5. Cyclic Nucleotide Assay

The AC activity of the purified recombinant AtMEE-AC was measured in vitro by incubating 5 µg of the protein in 50 mM Tris-Cl; pH 8.0, 2 mM isobutylmethylxanthine (IBMX, Sigma-Aldrich Corp., Missouri, USA) (to inhibit phosphodiesterases), 5 mM Mg2+ or Mn2+, 1 mM ATP with or without 10 mM NaF, in a final volume of 200 µl. Background cAMP levels in control reactions were measured in tubes that contained the incubation mediums but no protein or NaF. All incubations were performed at room temperature (24°C) for 20 min and terminated by the addition of 10 mM EDTA followed by boiling for 3 min and cooling on ice for 2 min before centrifugation at 2500xg for 3 min. The resulting supernatants were assayed for cAMP content using the cAMP-linked enzyme immunoassaying kit following its acetylation protocol and as is described in the supplier’s manual (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., Missouri, USA; code: CA201). The anti-cAMP antibody in this assaying system is highly specific for cAMP and has approximately a 106 times lower affinity for 3′,5′-cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP). In all cases, each experiment was performed in triplicate (n = 3) using three different protein extracts that were independently expressed and purified. Data was then analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc Student-Newman-Keuls (SNK) multiple range tests.

2.6. Complementation Testing

To validate the inherent AC activity of the cloned and expressed AtMEE-AC, an endogenous assaying test of this recombinant protein was carried out. In this test, competent SP850 mutant E. coli cells [lam-, el4-, relA1, spoT1, cyaA1400(::kan), thi-1] (Coli Genetic Stock Centre, Yale, USA), which cannot ferment lactose as a result of their deficiency in the AC (cyaA) gene and inability to produce the most wanted cAMP for this process [26-28], were transformed with the pCRT7/NT-TOPO:AtMEE-AC fusion construct followed by their growth onto MacConkey agar supplemented with 1% (w/v) lactose, 15 µg/ml kanamycin and 0.1 mM IPTG, at 37°C for 18 - 40 h. After incubation, the ability of the transformed mutant cells to now ferment lactose was then considered as an indication of the expressed recombinant AtMEE-AC’s ability to generate cAMP from ATP, as a functional AC. In this case, the transformed cells would turn deep red or purple, while control cells (mutant or wild-type cells not expressing the AtMEE-AC recombinant) would remain yellow or colourless.

2.7. Co-expressional Analysis of the AtMEE Gene

The Arabidopsis co-expression tool (ACT) (http://www.arabidopsis.leeds.ac.uk) [29] was used to perform correlation analysis, using At2g34780 as the driver gene. The analysis was performed across all available experiments, leaving the gene list limit blank to obtain a full correlational list. In this search, the 50 top co-expressed genes or expression-correlated genes (CEG50) were considered based on the Pearson correlation coefficient as a measure of similarity between them.

2.8. Stimulus-specific Microarray Expression Profiling of the AtMEE Gene and its CEG50

The expression profiles of the AtMEE-CEG50 gene set were initially screened over all available ATH1:22K arrays, Affymetrix public microarray data in the Genevestigator V3 (https://www.genevestigator.com) using the stimulus and mutation tools [30]. To obtain a greater resolution of the gene expression profiles, the normalized microarray data were subsequently downloaded and analyzed for experiments that were found to induce differential expression of the genes. The data were downloaded from the following repository sites; GEO (NCBI) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) [31], the NASCArrays (http://affymetrix.arabidopsis.info/narrays/experi mentbrowse.pl) [32], and the TAIR-ATGenExpress (http:// www.ebi.ac.uk/microarray-as/ae/). The downloaded array data were then analyzed and the fold-change (log2) values for each experiment calculated.

2.9. Promoter analysis of the AtMEE Gene and its CEG50 Gene Set

The promoter regions of At2g34780 and its CEG50 gene set were analyzed for any enrichment in potential transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) using the web-based Athena (http://www.bioinformatics2.wsu.edu/cgi-bin/Athena) [33] and POBO (http://ekhidna.biocenter.helsinki.ft/poxo/pobo) [34] applications. The visualization tool in Athena performs an analysis of Arabidopsis promoter sequences and reports the enrichment of known plant TFBSs. The analysis of the AtMEE-CEG50 was performed using settings of 1000 bp upstream of the transcription start site (TSS) and not cutting off at adjacent genes. The Athena results were subsequently confirmed in POBO by uploading promoter sequences 1 kb upstream of the coding region of the AtMEE-CEG50. The analysis was run against an Arabidopsis background (clean), searching for the MYB core motif (CNGTTR) using default settings. A two-tailed p-value was then calculated in the linked online GraphPad website using the generated t-value and degrees of freedom to determine the statistical differences between the input sequences and background.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Cloning, Expression, and Purification of AtMEE-AC and Determination of its AC Activity

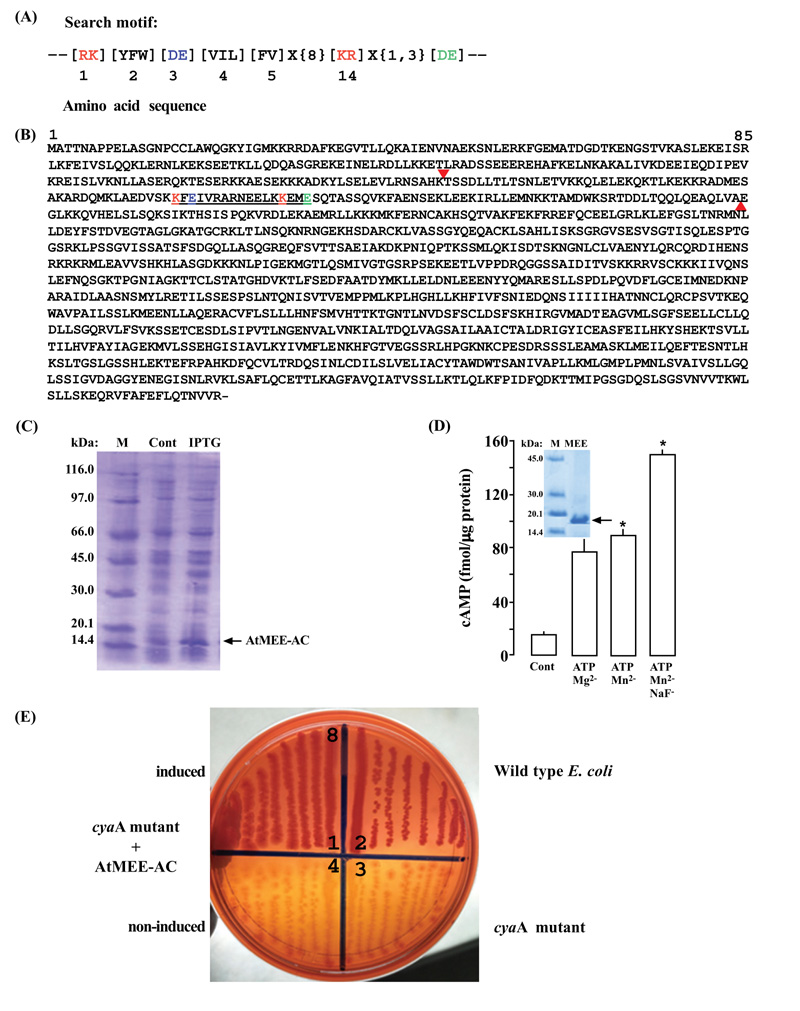

The identification of ACs in plants mostly involved querying protein sequences with the modified guanylyl cyclase(GC) search motif [35] at position 3, changing it from (CTGH) to (DE) [14] (Fig. 1A). This substitution is based on previous findings, which showed that the conversion of GCs into ACs and vice versa could be easily achieved through a single mutation in the amino acid that confers substrate specificity [36, 37]. When the AC motif queried the AtMEE sequence, a matching hit was detected towards its N-terminal end (amino acids 271 - 287) (Fig. 1B). A fragment sequence of the At2g34780 gene (amino acids 219 – 339) harboring the AC motif (Fig. 1B) was then cloned into a prokaryotic system and expressed into a 16.810 kDa AtMEE-AC His-tagged recombinant protein (Fig. 1C). To test if the AC centre of AtMEE can generate cAMP in vitro, the expressed recombinant AtMEE-AC was extracted and affinity purified (Fig. 1D inset). The AC activity of the purified recombinant was then tested in a reaction mixture containing ATP as substrate, Mn2+ or Mg2+ as cofactor, and NaF as a modulator, followed by measurement of cAMP by enzyme immunoassay. Maximum activity was reached after 20 minutes of the reaction system, generating about 76 fmols/µg protein of cAMP in the presence of either Mn2+ or Mg2+ and around 152 fmols/µg protein of cAMP when the reaction system was supplemented with NaF compared to only about 15 fmols/µg protein of cAMP of the control reaction (Fig. 1D). To investigate if the AC centre of AtMEE can rescue an E. coli AC-deficient mutant, the AtMEE-AC was cloned and expressed in an E. coli SP850 strain, lacking the AC (cyaA) essential for lactose fermentation [26-28]. As a result of the cyaA mutation, the AC deficient and uninduced transformed E. coli cells remained yellowish in colour when grown on MacConkey agar. In contrast, the AtMEE-AC-expressing SP850 cells formed deep reddish colonies much like the wild-type E. coli (Fig. 1E), thus indicating a functional AC center in the recombinant AtMEE-AC protein.

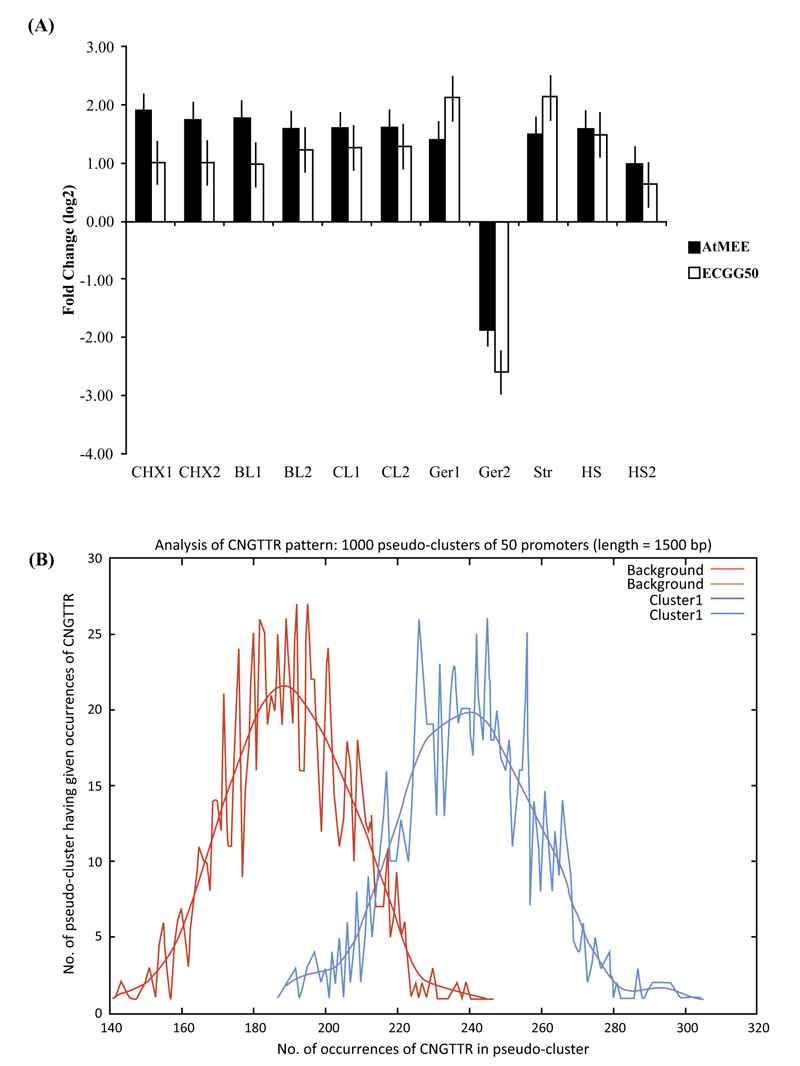

3.2. Stimulus-specific Expression and Promoter Profile of At2g34780 and its Correlated Genes

When At2g34780 was analyzed for co-expression in the Arabidopsis genome, we noted that 50 of its most correlated genes have high r values of between 0.80 and 0.87 (Appendix A, Table S1). These expression-correlated genes (CEG50) are also significantly enriched in the “biological process” gene ontology (GO) category ‘embryo development’ - a process that is essentially mediated by cAMP [38] and thus entirely consistent with the deduced catalytic activity of AtMEE as an AC (Fig. 1D and E). When we extended the analysis to identify conditions that induce At2g34780 and its CEG50, we noted induction by various factors such as desiccation and heat, thus proposing a role for AtMEE in abiotic stress (Fig. 2A). Finally, when we subjected At2g34780 and its CEG50 to promoter enrichment analysis, we found out that these genes have a common transcription factor binding site (TFBS) in their promoters (Fig. 2B) that then allows them to be co-expressed, co-regulated and ultimately, co-function. The identified common TFBS is the CNGTTR core element known to bind MYB transcription factors (TFs) [39] (Table 1).

| Rank | Locus and GO Termsa | r-value | Annotation and Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | AT2G34780 | 1.00 | Maternal effect embryo arrest 22 |

| 1 | AT3G66652 | 0.87 | Fip1 motif-containing protein |

| 2 | AT1G79490 | 0.86 | Pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) superfamily protein |

| 3 | AT1G52160RNAp, tRNAp | 0.85 | tRNAse Z3 |

| 4 | AT5G39960 | 0.85 | GTP binding protein |

| 5 | AT4G04670RNAp, tRNAp | 0.85 | Met-10+ like family protein/kelch repeat-containing |

| 6 | AT5G46920RNAp | 0.84 | Intron maturase, type II family protein |

| 7 | AT1G30240 | 0.84 | Binding protein |

| 8 | AT4G22285 | 0.84 | Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolases superfamily protein |

| 9 | AT5G14050RNAp, rRNAp | 0.84 | Transducin/WD40 repeat-like superfamily protein |

| 10 | AT4G31120 | 0.83 | SHK1 binding protein 1 |

| 11 | AT1G72440ESD, MG | 0.83 | CCAAT-binding factor |

| 12 | AT5G64420 | 0.83 | DNA polymerase V family |

| 13 | AT5G54910 | 0.83 | DEA(D/H)-box RNA helicase family protein |

| 14 | AT3G10530 | 0.83 | Transducin/WD40 repeat-like superfamily protein |

| 15 | AT5G18440 | 0.83 | Nuclear fragile X mental retard-interacting protein 1 |

| 16 | AT5G06350 | 0.82 | AT5G06350, ARM repeat superfamily protein |

| 17 | AT5G59980RNAp tRNAp, | 0.82 | Polymerase/histidinol phosphatase-like |

| 18 | AT3G49240 | 0.82 | Pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) superfamily protein |

| 19 | AT2G18220 | 0.82 | Noc2p family |

| 20 | AT3G56990ESD, MG | 0.82 | Embryo sac development arrest 7 |

| 21 | AT4G10620 | 0.82 | P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases |

| 22 | AT5G22840 | 0.82 | Protein kinase superfamily protein |

| 23 | AT1G15440 | 0.82 | Periodic tryptophan protein 2 |

| 24 | AT2G07750 | 0.82 | DEA(D/H)-box RNA helicase family protein |

| 25 | AT5G24840RNAp, tRNAp | 0.81 | tRNA (guanine-N-7) methyltransferase |

| 26 | AT1G71850 | 0.81 | Ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase family protein |

| 27 | AT5G38720 | 0.81 | Unknown protein. |

| 28 | AT3G48250 | 0.81 | Pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) superfamily protein |

| 29 | AT2G05120 | 0.81 | Nucleoporin, Nup133/Nup155-like |

| 30 | AT4G38890RNAp tRNAp, | 0.81 | FMN-linked oxidoreductases superfamily protein |

| 31 | AT2G01740 | 0.81 | Tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR)-like superfamily protein |

| 32 | AT3G16840 | 0.81 | P-loop containing nucleoside triphosphate hydrolases |

| 33 | AT1G17690 | 0.81 | Unknown protein |

| 34 | AT3G13940 | 0.81 | DNA binding/DNA-directed RNA polymerases |

| 35 | AT1G06220ESD, MG | 0.81 | Ribosomal S5/Elongation factor G/III/V family protein |

| 36 | AT4G19610 | 0.81 | Nucleotide binding;nucleic acid binding; RNA binding |

| 37 | AT1G02370 | 0.81 | Tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR)-like superfamily protein |

| 38 | AT4G02400RNAp rRNAp, | 0.81 | U3 ribonucleoprotein (Utp) family protein |

| 39 | AT3G16810 | 0.81 | Pumilio 24 |

| 40 | AT4G04940RNAp rRNAp, | 0.81 | Transducin family/WD-40 repeat family protein |

| 41 | AT4G21170 | 0.81 | Tetratricopeptide repeat (TPR)-like superfamily protein |

| 42 | AT5G39840 | 0.81 | ATP-dependent RNA helicase, mitochondrial, putative |

| 43 | AT5G17930 | 0.81 | MIF4G domain-containing/MA3 domain-containing |

| 44 | AT3G21540RNAp rRNAp, | 0.80 | Transducin family/WD-40 repeat family protein |

| 45 | AT1G08610 | 0.80 | Pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) superfamily protein |

| 46 | AT5G13680 | 0.80 | IKI3 family protein |

| 47 | AT3G01160 | 0.80 | Unknown protein |

| 48 | AT2G18330 | 0.80 | AAA-type ATPase family protein |

| 49 | AT3G11964RNAp | 0.80 | RNA binding; RNA binding |

| 50 | AT1G69070 | 0.80 | Unknown protein |

4. DISCUSSION

In Arabidopsis thaliana, the name maternal effect embryo arrest (MEE) is derived from a description of mutant screens (mee) of the Ds transposon insertion lines with defects in embryogenesis due to mutations in the female gametophyte [40]. A protein (AtMEE) associated with this kind of mutation is primarily expressed in the shoot apex [41] with function in the proper maintenance of shoot-apical meristems (SAMs) [42] - essential tissues from which all plant organs (leaves, stem, and floral parts) emerge and develop [43]. In plants and other organisms in general, development and cellular processes are primarily modulated by second messenger molecules such as the 3ʹ,5ʹ-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), generated by a special group of enzymes called adenylyl cyclases (ACs) [14, 44, 45]. However, while there is so much physiological and biochemical evidence for the role of cAMP in plants, the identification of ACs has largely remained slow [2, 14, 46]. Incidentally, in one previous study, AtMEE was annotated as an AC because of the existence of a putative AC catalytic center (Fig. 1A) [14] in its structure (Fig. 1B), commonly found in most experimentally tested and functionally confirmed plant ACs [1, 9, 15-22]. Thus, by considering this and the possibility that in A. thaliana, many ACs still remain to be identified [14], we decided to investigate if this AtMEE protein is indeed an AC.

We cloned a truncated version of the AtMEE (amino acids 219-339), harboring the annotated and predicted AC catalytic center (Fig. 1B), followed by expression (Fig. 1C) and purification (Fig. 1D, inset) of the generated recombinant protein (AtMEE-AC). When tested in vitro for AC activity, using an enzyme immunoassaying system, the purified recombinant AtMEE-AC demonstrated activity that was dependent on either the Mg2+ or Mn2+ metal ion and positively enhanced by NaF (Fig. 1D). This outcome then principally confirmed the membrane-bound localization of AtMEE [47] as a trans-membrane AC (tmAC) [48] because tmACs can flexibly work with either Mg2+ or Mn2+ as co-factor [49] and are functionally activated by the F- ion [49-51].

When expressed in SP850 host cells, AtMEE-AC complemented a catabolic defect (cyaA mutation) of this E. coli mutant strain that is associated with lactose fermentation (Fig. 1E). The SP850 host strain lacks the only AC system available in E. coli, necessary for the fermentation of lactose [26-28] and therefore, its rescue by AtMEE-AC to now ferment lactose, signifies the functionality of this putative protein as an AC. Ten out of the currently known eleven plant ACs have also demonstrated this capability [1, 15-24].

In eukaryotes, it is widely accepted that proteins that are co-expressed often have related functions and coordinated regulatory systems [52, 53], including linked physical interactions among themselves [54, 55]. Therefore, to explore and gain insights into the probable biological functions of the AtMEE protein, we subjected its gene (At2g34780) to expressional correlation analysis and stimulus-specific expression analysis. From these two analyses, it emerged that At2g34780 is mostly co-expressed with genes involved in embryo development (Table S1) and, together with its co-expressed partners, are differentially expressed in response to a wide range of abiotic stress factors such as heat and desiccation (Fig. 2A). Conceivably, this thus proposed a core function for the AtMEE protein in these two key cellular processes (embryogenesis and response to abiotic stress) that are both mediated by cAMP [14]. In addition, we further subjected At2g34780 to promoter enrichment analysis and found out that this gene, together with its co-expressed partners, have a common transcription factor binding site (TFBS) in their promoters (Fig. 2B) that then allows the AtMEE protein and its co-expressed protein partners to be co-regulated and ultimately co-function [55]. The identified common TFBS is the CNGTTR core element known to bind MYB transcription factors (TFs) [39]. Notably, MYB TF proteins have been strongly considered key regulatory factors controlling abiotic stress in plants [39], with their mechanism of action in A. thaliana believed to involve a typical binding of the CNGTTR cis core element of various proteins, thereby activating their regulation and downstream transcriptional and translational processes [56].

CONCLUSION

Our work has successfully identified an AC molecule, in the form of AtMEE, with key roles in embryo development and response to abiotic stress. This protein now becomes the seventh Arabidopsis AC and the eleventh-ever such molecule to be identified in plants. Interestingly, these crucial findings of our work also place AtMEE in a new group of plant ACs with roles in abiotic stress responses together with AtNCED3, ZmRPP13-LK3 and HpAC [21-23]. While AtMEE was herein shown to be involved in heat and desiccation stress, AtNCED3 is involved in ABA-mediated resistance to osmotic and salt stress [21], ZmRPP13-LK3 in ABA-mediated resistance to heat stress [22], and HpAC in responses to wounding or mechanical injuries [23]. Thus, considering the crucial role of this new group of plant ACs, which in essence, mitigates effects of the various environmental stress factors that commonly affect our important agronomic crops, it is prudent to strongly recommend for further characterization and manipulation of these proteins, especially their cAMP-dependent downstream signaling processes, to allow opportunities for the possible development of crop varieties or cultivars with increased tolerance to abiotic stress.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| cAMP | = cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate |

| AC | = Adenylyl Cyclase |

| AtMEE | = Arabidopsis MEE |

| VICs | = Voltage-Independent Channels |

AUTHOR’S CONTRIBUTION

OR conceived the idea and designed the experiments; DK, TD, and PC performed all wet-bench experiments, while DK, MT, EB, and KS performed all bioinformatics tasks. OR drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to the writing, revision, and approval of the manuscript's final version.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Not applicable.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

No animals/humans were used for studies that are the basis of this research.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of the article is available within the article.

FUNDING

This work was fully funded by the National Research Foundation (NRF) of South Africa - Grant Number: CSUR93635.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the support provided by the North-West University (NWU) in terms of research facilities and infrastructure. The authors also express their sincere gratitude for the financial support provided by the NRF, South Africa. However, it is clearly stated that any opinion, finding, conclusion, or recommendation expressed in this study is solely that of the author(s); therefore, the NRF, South Africa does not accept any liability in this regard.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available on the publisher’s website along with the published article.