All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Bacterial Cellulose from Food to Biomedical Products

Abstract

Cellulose production of aerobic bacteria with its very unique physiochemical properties attracted many researchers. The biosynthetic of Bacterial Cellulose (BC) was produced by low-cost media recently. BC has been used as biomaterials and food ingredient these days. Moreover, the capacity of BC composite gives the numerous application opportunities in other fields. Bacterial Cellulose (BC) development is differentiated from suspension planktonic culture by their Extracellular Polymeric Substances (EPS), down-regulation of growth rate and up-down the expression of genes. The attachment of microorganisms is highly dependent on their cell membrane structures and growth medium. This is a very complicated phenomenon that optimal conditions defined the specific architecture. This architecture is made of microbial cells and EPS. Cell growth and cell communication mechanisms effect biofilm development and detachment. Understandings of development and architecture mechanisms and control strategies have a great impact on the management of BC formation with beneficial microorganisms. This mini-review paper presents the overview of outstanding findings from isolating and characterizing the diversity of bacteria to BC's future application, from food to biosensor products. The review would help future researchers in the sustainable production of BC, applications advantages and opportunities in food industry, biomaterial and biomedicine.

1. INTRODUCTION

Microorganisms are usually defined with their planktonic and suspension cell growth characterizations. Attachment of microorganisms on the surface exhibited the specific phenotypes. These phenotypic distinctions are due to gene expressions and growth rate. Therefore, biofilms showed the unique surface attachment-detachment, community structure and finally micro-ecosystems. Bacterial cellulose (BC) is a natural nanomaterial of exopolysaccharide biofilm from many bacterial genera such as Acetobacter, Sarcina and Agrobacterium and Komagataeibacter (former Gluconacetobacter) [1]. Komagataeibacter can produce BC while cultivated in a medium supplied with carbon and nitrogen [2]. The priority of BC production by this genus is due to their higher yield and purity. However, the species and strains biofilm structure and mechanical properties are different [3].

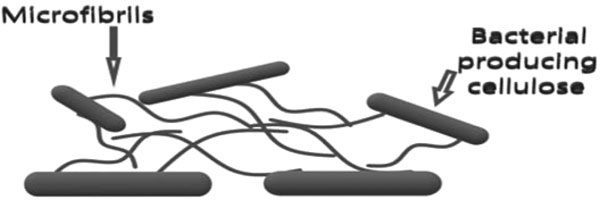

Chinese reported BC firstly during their ancient production of fermented beverage kombucha tea. They observed the co-colony of acidic acid bacteria and yeast embedded on the beverage surface [4]. Generally, the microbial biofilm and in particular, BC production are the self-defense strategy towards sustainable acquiring and securing nutrients supply in harsh environments [5]. Many multi-step regulated mechanisms with the help of enzymes and catalytic complexes rigorously control the cell's BC synthesis reactions. Although, 1,4-β-glucan chains formation and their assembly to cellulose inside and outside of the bacterial cell are the main two steps of BC synthesis [5-7] (Fig. 1).

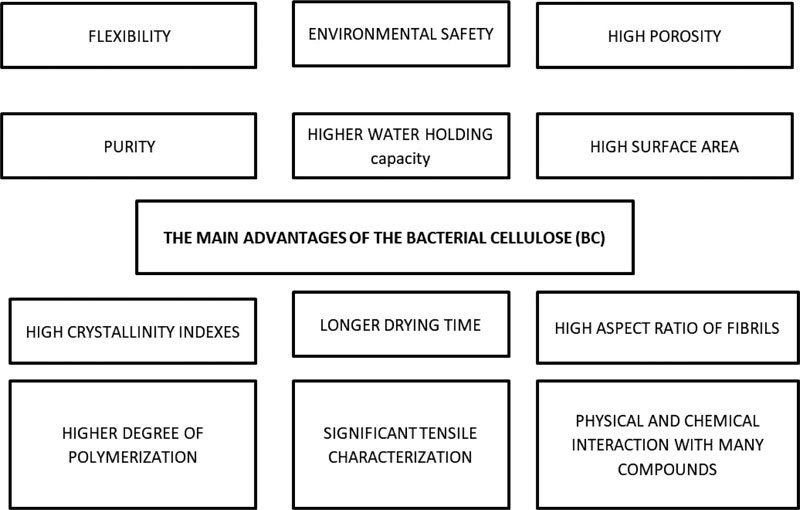

The main advantage of BC is the purity of cellulose. Impurities of lignin, hemicelluloses, and pectin in plant derived cellulose enforced the application of harsh chemicals in purification process (environmental safety); however BC purification process needs low energy [8, 9]. Unique properties of BC include crystallinity indexes up to 85% [10], a higher degree of polymerization, significant tensile characterization [11-13], a specific area in BC fibers, higher water holding capacity, and longer drying time [14-16]. These unique features are related to the high aspect ratio of fibrils, which made the increased surface area hold higher water capacity and tightly bound them to hydroxyl groups. BC generally is very flexible and easy to modify based on its many reactive groups. High porosity and surface area make BC appropriate for physical and chemical interactions with many compounds, including antimicrobials [10, 17, 18] (Fig. 2).

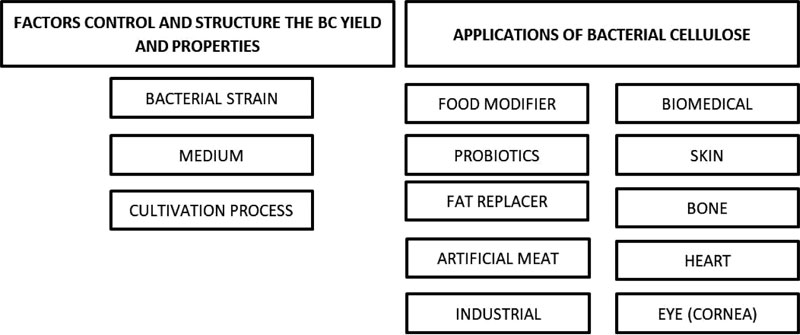

Many factors control and structure the BC yield and properties. Bacterial strains, medium composition and cultivation process mainly determine the morphology, properties and eventually range of possible application of BC. Several BC applications were recently developed, for example, biomedical applications of BC mostly focused on materials for tissue engineering, wound dressing, artificial skin, blood vessels, and carriers for drug delivery [1, 12] (Fig. 3).

Optimization of the production line from strain selection to final modification needs much effort in research. Achieving these goals attracted many researchers to explore better BC producing species/ strains and low-cost media. It is noteworthy to mention that replacing the expensive media Hestrin and Schramm (HS) has been done by many researchers [19-23]. However, the BC produced purity was in less degree as those required for some applications such as biomedical and industrial applications.

The production of cellulosic bacteria generally includes the two main steps, bacterial strain and bioprocess production. Static and stirred cultivation, besides semi-continuous or continuous fermentation methods, are the major bioprocess productions. The shapes and properties of final cellulose products are in significant dependence to the strain of bacteria, static, agitated, batch or feed batch production processes [24]. This review paper presents an overview of outstanding findings in BC production and applications.

2. STRAIN SELECTION

Naturally, the bacterial species of Achromobacter [25, 26], Alcaligenes [27], Aerobacter [28, 29], Agrobacterium [30-33], Azotobacter [6], Gluconacetobacter [19, 34, 35], Pseudomonas [36], Rhizobium [37, 38], Sarcina [39] and Dickeya and Rhodobacter [40] can produce cellulose.

However, the Gluconacetobacter genus is the primary group of BC producers. This fact is due to the wide range of carbon and nitrogen sources used by the Gluconacetobacter genus [7, 41]. In recent days with biotechnology, the engineered bacteria with low consuming nutrients and high yield were produced [41, 42]. For example, Komagataeibacter rhaeticus was engineered and fully sequenced with low nitrogen and high yield. It is noteworthy to mention that genetic tool kit was developed for this bacterium to engineer the desired bacteria recently [43].

3. GENETIC MECHANISMS OF CELLULOSE PRODUCTION

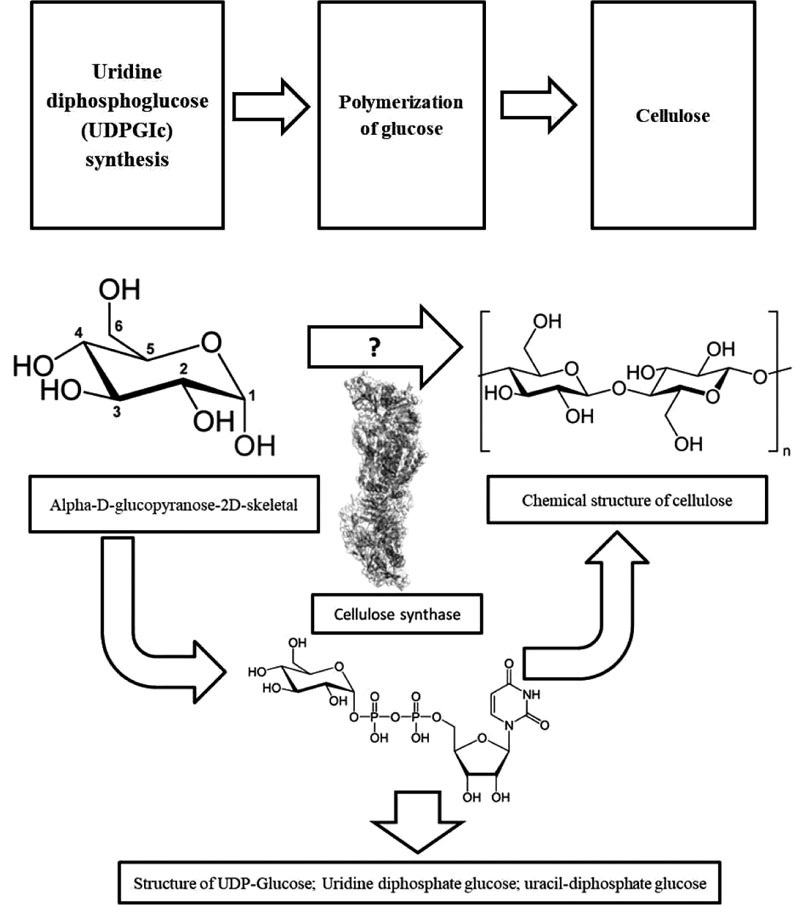

Uridine diphosphoglucose (UDPGIc) synthesis and polymerization of glucose are the two main cellulose production steps in bacteria. The polymerization is achieved by cellulose synthase, which formed an unbranched chain of 1,4-β-glucan. Naturally, carbon compound of hexoses, glycerol, dihydroxyacetone, pyruvate, and dicarboxylic acids entering the Krebs cycle, gluconeogenesis or the pentose phosphate cycle, followed by phosphorylation and isomerization and finally UDPGIc pyrophosphorylase converts the compounds into UDPGIc, a precursor for the cellulose production. The efficiency of this production is different in different bacteria, for example, for A. xylinum is 50% [27] (Fig. 4). Remarkable genetic engineering approach was presented recently. In this approach, the most efficient microbial BC producer, Komagataeibacter rhaeticus iGEM, was isolated, and its full genome was sequenced. This bacterium was then engineered for functionalization of cellulose production. The functionalization engineering results will help other researchers apply a similar method for producing the more specific BC with unique pattern for biomaterial applications [43].

4. CULTURE MEDIUM

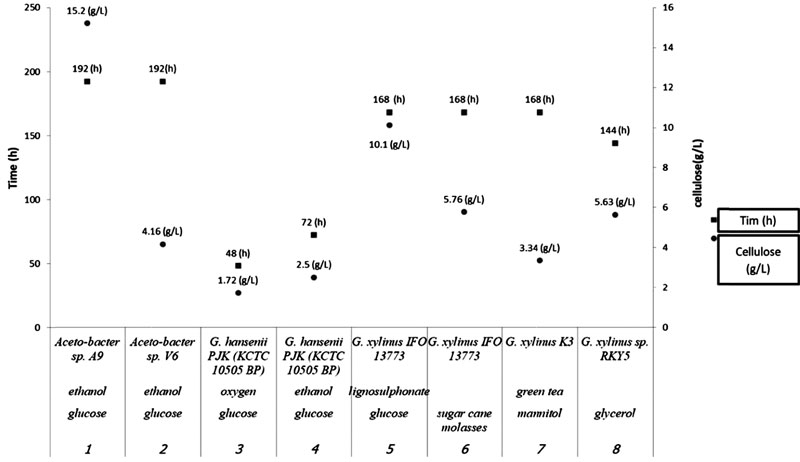

BC medium is costly, as it needs a high demand of glucose and other nutrients [44]. Hestrin and Schramm (HS) medium (glucose, peptone, and yeast extract) is used for BC production; however, the uses of the wastes, foods, and fruits as a medium have been reported recently [44-50]. For example, fruit juices such as orange, pineapple, apple, Japanese pear, and grape showed a higher yield in Acetobacter xylinum BC production [46]. Furthermore, other fruits such as pineapple, pomegranate, muskmelon, watermelon, tomato, orange, and also molasses, starch hydrolysate, sugarcane juice, coconut water, coconut milk were used as carbon sources [44]. The same properties of BC from these sources were reported with more expensive media [48]. Organic acid, carbohydrates, ethanol, and acetic acid, have been used as additives in BC production media [51, 52] (Fig. 5).

Optimization of the media during the process is the key to succeed in producing sustainable BC. Many factors such as pH, oxygen supply, and temperature should be controlled and optimized during the process [7, 41]. All of these factors affect the yield and properties of the final products. The pH and temperature are highly dependent to the species and strain of bacteria. Generally, pH could be between 4.0- 7.0. On the other hand, the pH of the culture can directly control the accumulation time and the secondary metabolite. This can affect nutrition supply in the process. For example, the dried weight of BC in Acetobacter xylinum 0416 was 60% higher in the control pH system compared to the uncontrolled. Furthermore, this bacterium's growth rate was 30% higher in lower pH conditions [53]. Also, aeration and oxygen optimization can play a critical role in BC production. Insufficient oxygen supply inhibits bacterial growth, and high oxygen supply favor gluconic acid production [7, 51, 54]. Temperature as an essential factor in BC production should optimize carefully. For example, optimal Komagataeibacter xylinus B-12068 temperature growth is preferably 28-30 °C [52] (Fig. 6).

5. CULTIVATION METHODS

The cultivation mode of the BC can be static or agitated. Static modes of cultivation usually take 5-20 days due to the bacterial strain and nutrients supply. The production is generally on the area of air/ liquid interface [24]. The final BC membrane shape depends on the material used for growing the BC in this method. This method used for the predefined shape of BC required. Disadvantages of this mode of action include low yield and more time consumption. [55, 56]. Fed-batch cultivation could help to overcome these problems [56]. Researchers showed two to three times' higher yields with fed-batch culture compared to batch cultivation [49]. Specific bioreactors were produced to use in the static mode culture of BC recently [57, 58]. Another mode of cultivation is agitated, which has a more oxygen supply therefore, the yield is higher than the static mode [59]. The shape of BC final product depends on the agitation speed. The drawback of the agitate mode of cultivation is the production of cellulose-negative mutants population. This mutant can produce BC with different properties as a subpopulation. To overcome this problem, the use of ethanol as a supplement nutrient is recommended [50, 58, 60, 61]. Stirred tank bioreactor can be used in the agitated mode for BC production. Shear stress is a great drawback of this BC production mode [62, 63]. Airlift bioreactor is another bioreactor with better efficient results [54]. In this bioreactor the oxygen supply is provided from the bottom of the tank, therefore preparing better BC production conditions [64].

6. SCRUTINIZING THE BC FORMATION: FROM PLANKTONIC CELL TO BIOFILM

Many researchers observed the biofilm in general with a simple microscope [65, 66]. However, the high-resolution electron microscope allowed us to examine the specific detailed characterizations of microbial biofilms [67]. It is noteworthy to mention that Ruthenium red (that stains the polysaccharide) facilitated the 'researcher's effort to show the matrix (structure) of biofilm based on the polysaccharide. Furthermore, the gene regulation studies and utilization of laser scanning microscope had a significant impact on understanding biofilm formation and characterization [67-69]. Traditionally biofilm is defined as the assemblage of 'microorganism's cells on the surface. This structure is irreversibly associated with themselves and the surrounding matrix. Biofilm matrix has a unique structure base on the cell and non-cellular materials of the medium. The main feature of biofilm is attachments that can be defined as unique substratum interactions, culture medium, hydrodynamic of aqueous environment and cell surface characteristics. These features are very important for scrutinizing the BC formation specifically and bacterial biofilm formation in general. Substratum is considered as the solid surfaces such as tissue, indwelling medical devices, industrial devices (piping), and natural aquatic systems. The physiochemical features of the surface play an important role in attachment; these features can effect on rate and extent of biofilm formation. Rough hydrophobic nonpolar surfaces are more favorable for rapid biofilm formation [70-74]. It is important to note that the surface of materials in an aqueous environment could facilitate and increase biofilm formation speed [75, 76]. The hydrodynamic of the environment with flow velocity could control biofilm formation (the higher velocity made thinner biofilm boundary layer). Furthermore, the settle down of cell suspension in the aqueous medium can control flow velocity [77-79].

The medium characteristics have a great impact on biofilm formation. pH, nutrient level, and temperature can play a substantial role in forming biofilm [80-84]. It is important to recall here that bacterial cell surface properties such as hydrophobicity and flagella influence the attachment and rate of biofilm formation. Furthermore, the production of EPS has a great impact on biofilm development [85-88]. Genes regulations have a countless effect on biofilm formation; for example, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa algC gene up regulation was observed during the bacterial attachments [89].

Moreover, polyphosphokinase synthesis genes in Pseudomonas aeruginosa were up-regulated [90]. The up-regulated genes in Staphylococcus aureus genes involved in the glycolysis pathway was reported previously [91]. The detailed information on gene regulation of biofilm formation was reviewed earlier [91].

7. DOWNSTREAM PROCESSING

These parts of the production consist of separation of BC from media and purification of biopolymers. The BC can remove easily from static mode cultivation by separation. In agitated mode BC removes from the media by centrifugation or filtration. The alkali treatment will do the purification of cellulose with NaOH or KOH [5, 6]. The level of purification is depending to the final application, for example we need more purify cellulose for biomedical applications compare to the food application. Sometimes drying step adds to the downstream process. Three kinds of room, oven, freeze and supercritical drying methods were used in this step. Drying can change BC's characteristic; therefore, it should be chosen very carefully [92].

8. FORMS OF BACTERIAL CELLULOSE

Intact membrane, disassembled BC and BC nanocrystals are three BC forms [41, 93, 94]. An intact membrane can be immersed in dispersion with other materials. This has the advantage of simpler disintegration from other materials but cannot change the fermentation process [50, 93, 94]. BC membrane on the other hand, can be disassembled, and therefore they are easier to integrate with other materials and even become better powder and film [95-97]. BC nanocrystal has been produced by acid hydrolysis, which removes the amorphous of the cellulose [98].

9. STRUCTURE OF BACTERIAL CELLULOSE

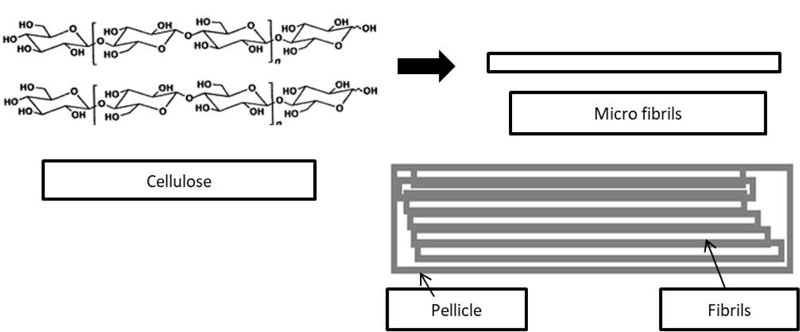

Cellulose indeed is polysaccharide consisting of carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen. This carbohydrate polymeric structure composes of glucose units. The role of cellulose in the bacterial film is stability towards different chemical or temperature environments. High mechanical strength, crystallinity, and ultra-fine and pure fiber network are very dependent on highly insoluble and inelastic cellulose fibrils. Pore and tunnels within the thin layer (pellicle) of bacterial cellulose can retain water 16 times higher than plant cellulose [99].

The cellulose pellicle was formed on the upper surface of air/ media, which shows the importance of oxygen for this process. The pellicle of bacterial cellulose with 15 GPa (Young modulus) [100] is considered as a very tough polymeric film. This unique structure is related to fibrils conformation, which is bound tightly by hydrogen bonds. The supermolecular structures of aligned glucan chains with inter and intrachain hydrogen bonds formed the microfibrils (Fig. 7). These microfibrils randomly assemble the fibrils, which literally construct the bacterial cellulose pellicle. It is noteworthy that bacterial cellulose belongs crystallographically to Cellulose I, which means the crystalline fibrils are in parallel arrangement [101]. Various types of irregularities of fibrils structures of cellulose (kinks or twists of the microfibrils and capillaries) provide the structural heterogeneity with much greater surface area compared to smooth fiber (Fig. 7).

10. MAIN APPLICATIONS OF BC

BC is recognized by the US food and drug administration as generally safe (GRAS) food [16]. As a fiber, BC is considered good indigestible food and prescribed in humans as dietetic food [102, 103]. One of the most famous BC is Nata-de-coco, which is the BC grown from coconut water with carbohydrates and amino acid. This cubic BC is immersed in sugar syrup [104].

The product export reached 6.6 billion USD in 2011 [105]. This kind of BC can be considered low calorie desserts / snacks and plays a great role as a novel foamy and crunchy product. On the other hand, the fats in the food are always associated with several health problems such as obesity, diabetes, high blood cholesterol levels, and heart diseases, therefore, replacing the fat with BC can help to improve the food industry and human health [106-108]. BC is already used in meatballs upto 20% or 10% [42, 55].

Meat is analogous with BC and the mold Monascus purpureus was prepared and introduced with many advantages such as antihypercholesterole. This Monascus-BC complex can be a good substitute for consumers with special dietary restrictions [58, 109, 110]. Furthermore, BC was used as a thicker food product to increase the strength in gelling products and water binding. Also, it was applied as a stabilizer of Pickering emulsions [13, 111]. As an immobilizing agent of probiotics and enzyme, BC also has great attention for many researchers [112, 113]. It is noteworthy to mention that lipase, laccase and lysozyme immobilized by BC were reported by researchers [114-116].

BC applications in food packaging as a film and coating were also reported by many researchers [117]. Impregnating BC with other polymers could bring many advantages to the composites. BC-chitosan produced by researchers recently showed the antimicrobial activity against gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria beside the better elastic property [118].

In the biomedical application of BC, several BC-composites were developed by researchers. The wound healing, skin and tissue regeneration, healing under infectious environment, development of artificial organs, blood vessels, skin substitutes, and many devices such as conducting devices, displays, optoelectronics, sensors and biosensors have been reported recently [18, 102, 119, 120].

CONCLUSION

Many challenges need to be addressed in BC research, such as introducing low-cost medium and efficient producing system with low capital investment. Besides many applications of BC and BC-composites, the need to study bacterial diversity is necessary. Furthermore, the study of 3-D printing of BC for food and food packages with specific geometry can provide more information in this field. Additionally, BC producers' diversity and molecular characterization can give great insight on low cost production of BC, especially for food and biomedical products. Last but not least, engineering the BC producers towards specific functionalization can answer many industrial and biomedical needs. Tunable control on BC production and novel structural pattern can be important for BC producer bacteria's future engineering.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

FUNDING

This work was financially supported by the Institute For Research and Development, Suan Sunandha Rajabhat University (SSRU) (Grant number 441/2563).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Anat Thapinta, Dean of the Faculty of Science and Technology, SSRU and Dr. Suwaree Yordchim, Director of the Institute of Research and Development, SSRU for their outstanding support. Wirongrong Thamyo is acknowledged for excellent secretarial assistance.