All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

In vivo Evaluation of the Repellency Effects of Nanoemulsion of Mentha piperita and Eucalyptus globulus Essential Oils against mosquitoes

Abstract

Introduction:

The present study aimed to prepare Nanoemulsions of Mentha piperita and Eucalyptus globulus essential oils and comparison of the repellant activity of them with normal essential oils and DEET in the field conditions.

Methods:

To determine the protection and failure time of the essential oils and DEET in the field condition against natural population of night biting culicid mosquitoes, 4 human volunteers participated in night biting test. GC-MS was used to determine the essential oil components and the Dynamic Light Scattering device was used to measure droplet size and zeta potential.

Results:

The relative abundance of more common species captured in this study was 40.09% and 31.65% for Anopheles superpictus, and Culex pipiens, respectively. Based on the results, the protection time of nanoemulsions of M. piperita 50% against night biting mosquitoes was 4.96±0.21 h. Also, the protection for nanoemulsions essential oil 50% of E. globulus was 6.06±0.20 h. Comparison of the results showed that the protection time of nanoemulsions of M. piperita and E. globulus was significantly higher than of their normal essential oils (P˂0.01). Also, the protection time of DEET (as a gold standard) was significantly higher than of normal essential oil and nanoemulsions of M. piperita (P˂0.01), but there is no significant difference between DEET and nanoemulsions of E. globulus (P˃0.01).

Conclusion:

Due to the safety and biocompatibility of the nanoessential oils, and also relatively adequate and acceptable protection time, nanoemulsions of E. globulus and probably M. piperita can be considered as good repellents. It is recommended to do more research on these nanoemulsion repellents, as they may be good alternatives to DEET.

1. INTRODUCTION

Insect-borne diseases are one of the major health problems in the tropical and subtropical regions of the world and mosquitoes are the main vectors of many of these diseases [1]. Mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria, yellow fever, filariasis, Dengue, chikungunya, haemorrhagic fever and encephalitis, annually cause extensive injuries and many deaths worldwide [2, 3]. The best way to control and manage mosquito-borne diseases is to prevent mosquito bites and control the vectors that cause them; therefore, the use of mosquito repellent compounds is very important in preventing these diseases [4]. Synthetic chemicals such as N, N-diethyl-m toluamide (DEET) has been used for many years as a mosquito repellant in most parts of the world because of its relatively long protection time. However, the results of various studies have shown that most of the chemicals synthesized, such as DEET, cause irreparable damage to the environment and show high permeability to the skin [5, 6]. Therefore, concerns about the harms of using synthetic chemicals are increasing [7]. According to the aforementioned, the use of safe and secure compounds such as herbal essential oils can be extremely important given their environmental degradation and repellency activity [8].

Essential oils are volatile mixtures of organic compounds and aromatic substances related to those compounds are secondary metabolites of the plant [9]. To date, more than 3,000 essential oils from various plants have been studied, approximately 10% of which have been commercialized and their repellent and lethal properties have been demonstrated against insects [10, 11]. The compounds of these essential oils play an important role in the repellent and lethal effects of essential oils against insects, and are the compounds that characterize the essential oil as having antioxidant, antimicrobial, medicinal, repellant, and lethal properties [12, 13]. A review of recent studies shows that citronellol, citronellal, -pinene and limonene are very common compounds in various plant essential oils that produce repellent properties [8, 14]. Moreover, these bioactive compounds are also in the hydrosols coproduced during water or steam distillation of plant materials [15].

Various methods have been proposed to increase the effectiveness of essential oils, such as the combination of several essential oils (a synergist) [13, 16, 17]. Also, the preparation of microencapsulation and nanoemulsification formulation can increase the repellency effects of essential oils [18, 19]. Recent studies have shown that nanotechnology can be very useful in enhancing the effectiveness of essential oils and significantly increases its repellent activity [20]. In a recent study, it has been shown that the preparation of nanoemulsion formulation of E. globulus and M. piperita essential oils increased their repellency effects and protection time against mosquitoes [21]. Therefore, given the improvement of the repellent activity of the essential oils due to nanodevelopment, as well as the fact that most of the repellent studies are carried out in the laboratory, the present study aimed to prepare Nanoemulsions of E. globulus and M. piperita essential oils and comparison of the repellant activity of these Nanoformulated essential oils with normal essential oils and DEET (Gold Standard) against mosquitoes in the field conditions.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this study, the repellant activity of M. piperita L. and E. globulus L. essential oils were investigated. It should be noted that both essential oils were obtained from the Zardband medicinal plants Inc. in Iran. Other materials used in this study, such as: N,N-diethyl-m toluamide (DEET) (with CAS NUMBER:134-62-3 and density 0.99 g⁄mL), ethanol, polysorbate 80, polyethylene glycol, and butanol were procured from Merck Chemicals Inc. in Germany.

2.1. GC–MS Analysis

The essential oils of M. piperita L. and E. globulus L. were analyzed by Agilent 6890N model GC-MS coupled with Agilent 5973 mass spectrometer that was located at the Faculty of Chemistry, Tabriz University. The carrier gas used in this device was helium (He 99.99%).

2.2. Preparation of Nanoemulsions

For preparation of Nanoemulsions, bipolar polyethylene glycol was used as a preservative, coating and a better cross-linking of essential oils as well as emulsifiers. Studies have shown that polyethylene glycol has medicinal use and is not harmful to humans [22]. Polysorbate 80 is a nonionic surfactant and was used as an emulsifier in this study. Nonionic surfactants, such as polysorbate, reduce the susceptibility of the compound to oxidation and make them more stable than other compounds [23]. Another material used in this study for the preparation of Nanoemulsions was Sesamum indicuml L. oil. This oil was used as a synergist and carrier of the essential oil. Various studies have shown that the use of oils with essential oils has a synergistic effect on the essential oils and increases their effectiveness [24]. For the preparation of nanoemulsion from essential oils of M. piperita and E. globulus, first, 13 cc (21%) of polyethylene glycol, slowly, was poured into a beaker under the homogenizer of model MICCRA D9 45043 with a round (11000 rpm) and then 10 cc (16%) of polysorbate 80, drop by drop was added to the polyethylene glycol under the homogenizer to dissolve the two substances well at a rate of 11000 rpm for 5 minutes. The amount of 5 cc (8%) of Sesamum indicuml oil was added to the two precursors, as a carrier and synergite oil and homogenization continued until well dissolved and combined. Then 30 cc (50%) of pure M. piperita or E. globulus essential oil was added to it and homogenizer continued until the ingredients were homogenized well. After about 10 minutes of rest, 2 cc (5%) of butanol was added and placed under homogenizer with round 11000 rpm for 5 min.

2.3. Measuring Droplet Size and Zeta Potential of the Nanoemulsion

Nanotrac Wave (Microtrac Inc.) DLS (Dynamic Light Scanning) with a measuring range of 8-6500 nm and a zeta potential measuring range of 20-200 mV was used to measure the droplet size and zeta potential nanoemulsion in the Central Laboratory of Tabriz University.

2.4. Investigating the Repellent Activity of Essential Oils and DEET in Field

Repellent activity of essential oils was investigated in an area of East Azerbaijan province (Tabriz city, 38°07' N, 46°15' E) in the northwest of Iran, where the in a place where the abundance of culicided mosquitoes was high. The repellents used in this study were: M. piperita 50%, E. globulus 50%, M. piperita Nano 50%, E. globulus Nano 50%, and DEET 25% as a gold standard. Ethanol was used to prepare the essential oils of 50% and DEET 25%. Repellent activity of essential oils and DEET were performed on 4 human volunteers with a mean age of 33 (SD±2.1) years. All parts of the volunteers’ body were covered (except for the part under study) and then the volunteers’ hand were smeared with repellants (1.5-2 mL) from the elbows to the wrists by a sampler. It should be noted that pure ethanol was used as a control to study the repellent activity of essential oils and DEET. The volunteers were spaced 5 meters apart to avoid the effects of repellent from one compound over another. Treatments were also randomly assigned to the volunteers, and the shift was assigned to all volunteers with 4 replications. The test locations of the volunteers were moved to different nights, and each volunteer was assigned to different locations at different nights. The mosquitoes were collected from the volunteer hand through an aspirator, and the mosquitoes were collected from the volunteers for the first 20 minutes and rested after 40 minutes, alternately. The test process, 20 minutes of sampling and 40 minutes of rest continued until the tenth bite (failure time) and no bites were observed [25]. The specimens collected through the aspirator were transferred to cups covered by mesh. The collected samples were then transferred to the laboratory and identified.

2.5. Species Identification

The mosquitoes were identified using valid Culicidae systematic keys, checklists and species description and illustrations [26, 27].

2.6. Statistical Analysis of Data

In this study, SPSS version 16 was used to analyze the data. The mean ± Standard deviation (SD) of protection time and failure time was also presented. Also, ANOVA, Tukey test was used to compare the means obtained in this study and 1% was considered as the significance level.

3. RESULTS

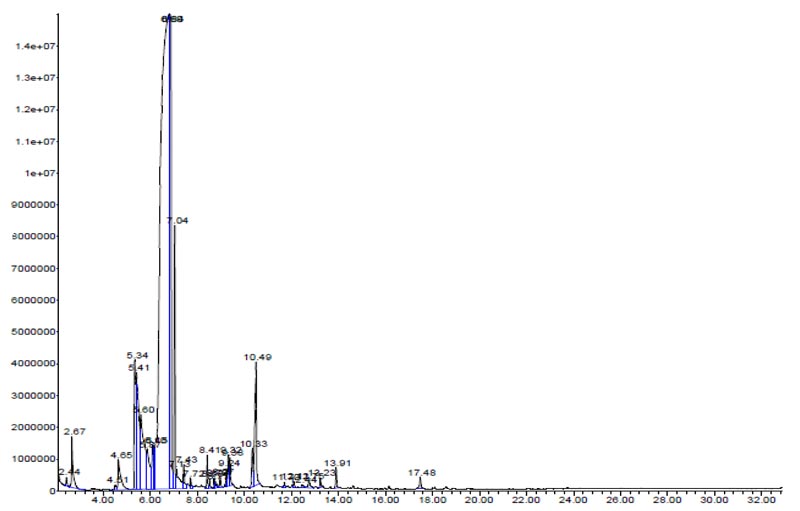

3.1. GC-MS Analysis

Analysis of GC-MS results showed that the main components of the M. piperita were: D-Limonene (19.7%), Thymol (19.0%), Carvacrol (12.4%) and Menthyl acetate (4.3%) (Fig. 1). Also in the case of E. globulus, essential oil components were: 1,8-Cineole (59.5%), Terpinene <γ-> (10.9%), Sabinene (5%), Pinene <β-> (4.4%), Terpinolene (3.4%) and Pulegone (3.1%) (Fig. 2).

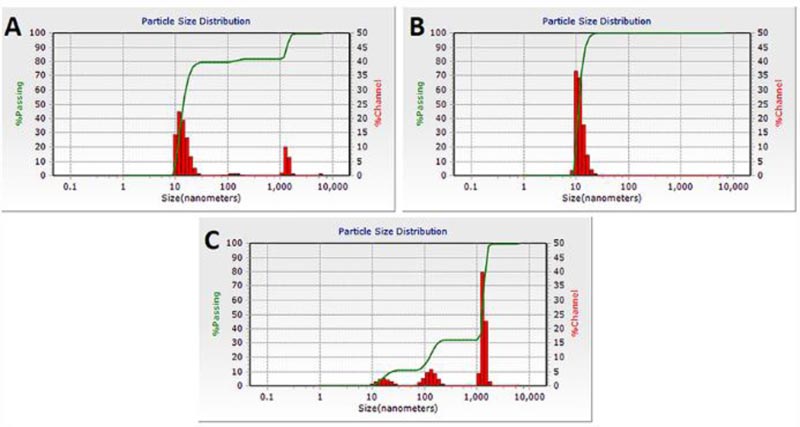

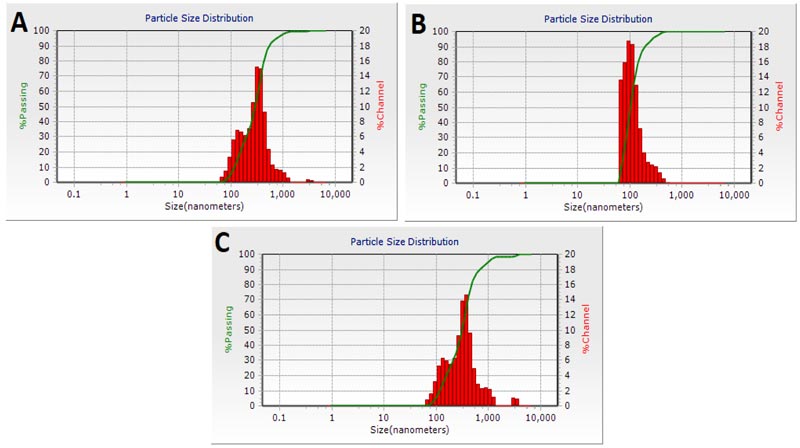

3.2. Measurements Droplet Size and Zeta Potential of Nanoemulsions

The results of this study showed that for M. piperita Nano, droplet size was about 11.32 nm on average. Zeta potential also obtained 9.5 mv for M. piperita Nano. About the E. globulus Nano, the droplet size was calculated to be about 103.9 nm on average. The zeta potential obtained for this essential oil was reported to be 27.0 mv. Particle size distribution profile of the M. piperita Nano and E. globulus Nano are presented in Figs. (3 and 4) by volume, number, and intensity.

3.3. Mosquitoes Identification

Identification of the collected culicidae mosquitoes in the night biting test showed that most abundant belonged to Anopheles superpictus (n=342 (40.09%)) and Culex pipiens (n=270 (31.65%)), respectively (Table 1).

| Total (%) | Number | Species name | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Case | ||

| 68 (7.97) | 59 | 9 | Anopheles maculipennis Meigen, 1818 |

| 342 (40.09) | 296 | 46 | Anopheles superpictus Grassi, 1899 |

| 270 (31.65) | 234 | 36 | Culex pipiens Linnaeus, 1758 |

| 173 (20.28) | 150 | 23 | Culex theileri Theobald, 1903 |

| 853 (100) | 739 | 114 | Total |

3.4. Protection Time

Analysis of the results of this study showed that the protection time of M. piperita 50% was in the ranges of 2.1-3 h, with an average of 2.57±SD=0.25 h; M. piperita Nano 50% was in the ranges of 4.5-5.3 h, with an average of 4.96±0.21 h; E. globulus 50% was in the range of 0.9-1.4 h, with an average of 1.1±0.15 h; E. globulus Nano 50% was in the ranges of 5.8-6.4 h, with an average of 6.06±0.20 h; and DEET 25% was in the ranges of 6-6.5 h, with an average of 6.25±0.14 h. Comparison of the results showed that the protection time in M. piperita Nano 50% and E. globulus Nano 50% was significantly higher than normal essential oils (P˂0.01). Also, the calculated protection time for DEET 25% was significantly higher than M. piperita 50%, M. piperita Nano 50% and E. globulus 50%, but the protection time difference between DEET 25% and E. globulus Nano 50% was not significant (Fig. 5).

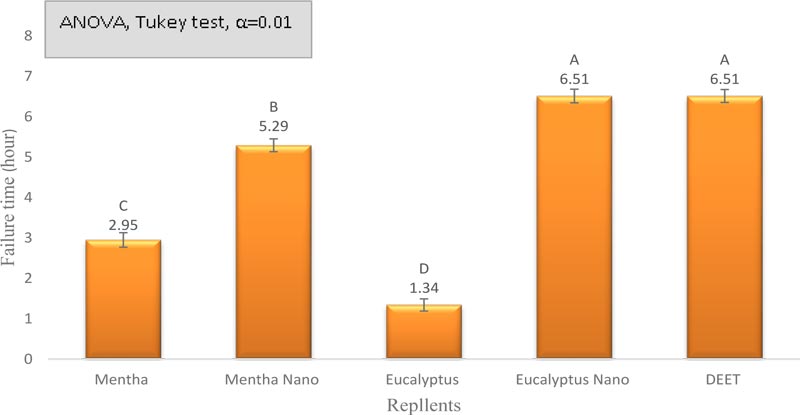

3.5. Failure Time

Failure time obtained for M. piperita 50% was in the ranges of 2.5-3.2 h, with an average of 2.95±SD=0.18 h; for M. piperita Nano 50% in the ranges of 5.1-5.9 h and average of 5.29±0.16 h; for E. globulus 50% in the ranges of 1.1-1.7 h, and average of 1.34±0.15 h; for E. globulus Nano 50% in the ranges of 6.2-6.8 h, and average of 6.51±0.17 h; and for DEET 25% in the ranges of 6.2-6.8 h, and average of 6.51±0.16 h. Comparison of the results of failure time showed that the failure time in M. piperita Nano 50% and E. globulus Nano 50% was significantly higher than normal essential oils (P˂0.01). Also, the calculated failure time for DEET 25% was significantly higher than M. piperita 50%, M. piperita Nano 50% and E. globulus 50%, but the failure time difference between DEET 25% and E. globulus Nano 50% was not significant (Fig. 6).

4. DISCUSSION

Mosquitoes are vectors of various dangerous diseases to humans, most of which lack vaccines and specific treatments. Therefore, the use of repellents can be an important method in the prevention of mosquito-borne diseases. In most cases, chemical and synthetic compounds are used as mosquito repellents that can cause significant damage to the environment and humans. Therefore, the use of herbal essential oils as a suitable and safe alternative to synthetic and chemical repellents is inevitable [13]. Essential oils extracted from various plants are, in most cases, not directly usable due to chemical instability, volatility, and tendency to oxidation, and modifications must be made to overcome these problems [28]. One of the best solutions to these problems is the use of Nanotechnology [19]. In this regard, nanoemulsions characterized by higher surface area-to-mass ratios can be considered a tool for delivering bioactive compounds [29].

Therefore, the present study aimed to prepare Nanoemulsions from M. piperita and E. globulus essential oils and to compare the repellent activity of these Nanoformolated essential oils with normal essential oils and DEET (Gold Standard) on Culicidae mosquitoes in the field on human subjects.

The results of the present study showed that preparation of Nanoemulsion from M. piperita essential oil increased the protection time of this essential oil compared to its normal formulation, from 2.57 to 4.96 hours and its failure time from 2.95 to 5.29 hours. In fact, the results of this study show that the preparation of Nanoemulsion from M. piperita essential oil increases twice its protection time and failure time. Also, the results of this study on E. globulus essential oil showed that the preparation of Nanoemulsion from this plant increased its protection time from 1.1 to 6.06 hours and its failure time from 1.34 to 6.51 hours. In the case of this essential oil, the results show that the preparation of Nanoemulsion from this essential oil was able to increase protection time and failure time, by up to 6 times. In a study consistent with the present study, Nuchuchua et al. [5] reported that preparation of Nanoemulsion from citronella, hairy basil and vetiver essential oils increased their protection time of these essential oils to 4.7 hours. In a similar study by Sakulku et al., the results showed that the preparation of Nanoemulsions from citronella essential oil and the addition of glycerol greatly improved the physical appearance and stability of the emulsion and increased its protection time [30]. In another similar study, Mohammadi et al. [21] reported that the preparation of Nanoemulsion from M. piperita and E. globulus significantly increased their protection and failure time. It should be noted that all the above mentioned studies have been carried out in the laboratory, and all conditions in the lab are under control, but in the environment, conditions are not under control and can produce different results.

The results of this study indicate that preparation of Nanoemulsion from M. piperita and E. globulus (especially Eucalyptus Nano) have protection and failure time similar to DEET and can be a suitable alternative to this harmful chemical compound. In a similar and consistent study, Navayan et al. reported that the preparation of microemulsion from E. globulus essential oil, significantly increased its protection time compared to normal E. globulus essential oils [31]. The results of the studies by Navayan et al. showed that E. globulus Nano and DEET have a similar protection time and E. globulus Nano could be a good alternative to this harmful compound [31]. A review of the results of various studies shows that the protection time obtained from DEET at concentrations 20% to 30% is 6-7 hours on average [21, 31]. According to the protection time obtained from the present study for E. globulus Nano in the field (about 6 h), so E. globulus Nano can be a good alternative for DEET.

CONCLUSION

Preparing Nanoemulsions from E. globulus and M. piperita Essential Oils significantly enhances their protection and failure time in the field and resembles the effectiveness of DEET. Therefore, due to the safety and biocompatibility and also relatively adequate and acceptable protection time, nanoemulsions of E. globulus and probably M. piperita can be considered as good repellents. It is recommended to do more research on these nanoemulsion repellents, in terms of safety and side effects, repellency characteristics and the possibility of improving the quality of these, nanoemulsions repellants, acceptability by the user, as they are likely to be a good alternative to DEET.

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

This study was approved with the Code of Ethics IR.Bmsu.REC.1396.202 by the Ethics Committee of Baqiyatallah University of Medical Sciences in Tehran, Iran.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All human research procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the committee responsible for human experimentation (institutional and national), and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Prior to the repellent tests, the objectives of the study were fully explained to the volunteers, and informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data related to the results of this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

FUNDING

None

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors are thankful to the Department of Entomology, Tarbiyat Modares University, for providing necessary laboratory facilities to conduct this research.